An Introduction to Lock-Free Programming

what is it

Nobody expects a large application to be entirely lock-free. Typically, we identify a specific set of lock-free operations out of the whole codebase. For example, in a lock-free queue, there might be handful of lock-free operations such as

Nobody expects a large application to be entirely lock-free. Typically, we identify a specific set of lock-free operations out of the whole codebase. For example, in a lock-free queue, there might be handful of lock-free operations such as push,pop, perhaps is_empty, and so on.

techniques

It turns out that when you attempt to satisfy the non-blocking condition of lock-free programming, a whole family of techniques fall out: atomic operations, memory barriers, avoiding the ABA problem, to name a few. This is where things quickly become diabolical.

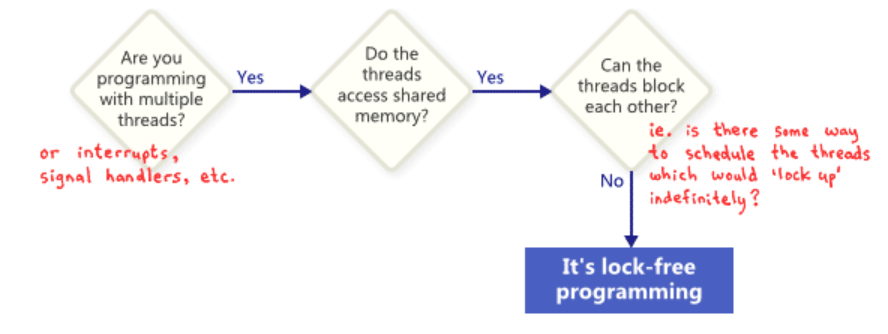

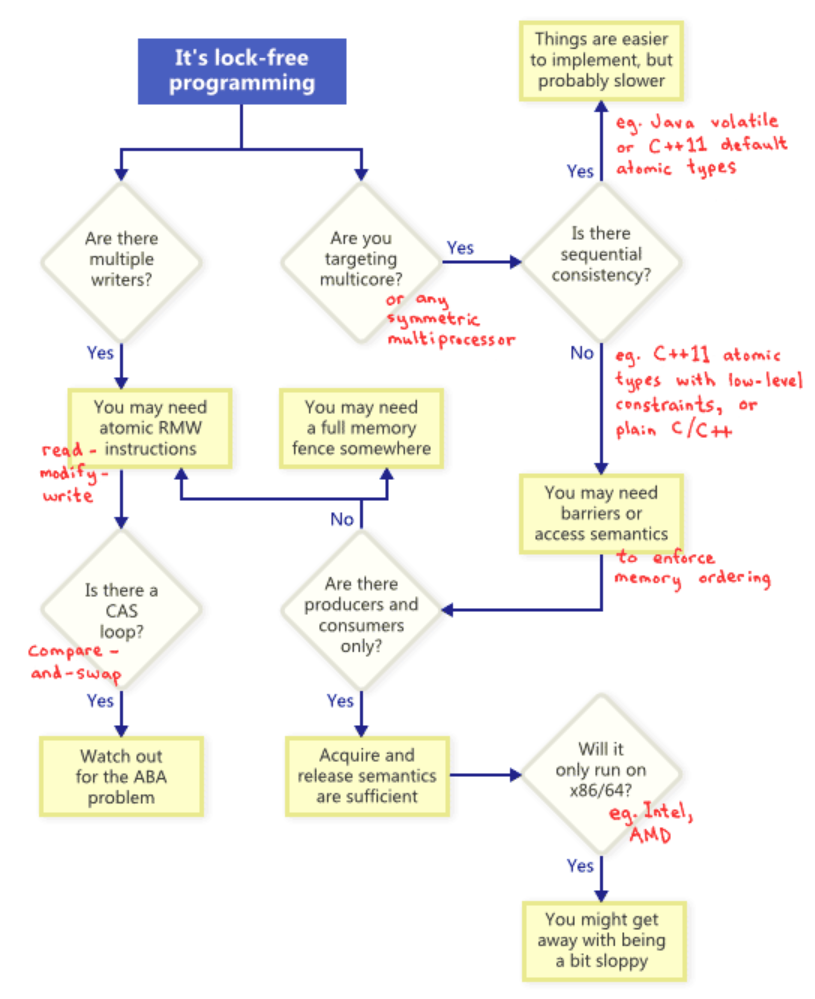

So how do these technique relate to one another? to illustrate, the following flowchart.

Atomic Read-Modify-Write operations

Atomic operations are ones which manipulate memory in a way that appears indivisible: No thread can observe the operation half-complete. On modern processors, lots of operations are already atomic. For example, aligned reads and writes of simple types are usually atomic.

Read-modify-write(RMW) operations go a step further, allowing you to perform more complex transactions atomically. They’re especially useful when a lock-free algorithm must support multiple writers, because when multiple threads attempt an RMW on the same address, they’ll effectively line up in a row and execute those operations one-at-a-time.

Examples of RMW operations include std::atomic<int>::fetch_add in C++11. Be aware that the C++11 atomic standard does not guarantee that the implementation will be lock-free on every platform. You can call std::atomic<>::is_lock_free to make sure.

As illustrated by the flowchart, atomic RMWs are a necessary part of lock-free programming even on single-processor systems. Without atomicity, a thread could be interrupted halfway through the transaction, possibly leading to an inconsistent state.

compare-and-swap loops

Perhaps the most often-discussed RMW operation is compare-and-swap (CAS). Often, programmers perform compare-and-swap in a loop to repeatedly attempt a transaction. This pattern typically involves copying a shared variable to a local variable, performing some speculative work, and attempting to publish the changes using CAS.

void LockFreeQueue::push(Node* newHead)

{

for (;;)

{

// Copy a shared variable (m_Head) to a local.

Node* oldHead = m_Head;

// Do some speculative work, not yet visible to other threads.

newHead->next = oldHead;

// Next, attempt to publish our changes to the shared variable.

// If the shared variable hasn't changed, the CAS succeeds and we return.

// Otherwise, repeat.

if (CAS(&m_Head, newHead, oldHead) == oldHead)

return;

}

}Whenever implementing a CAS loop, special care must be taken to avoid the ABA problem.

Sequential consistency

Sequential consistency means that all threads agree on the order in which memory operations occurred, and that order is consistent with the order of operations in the program source code.

A simple (but obviously impractical) way to achieve sequential consistency is to disable compiler optimizations and force all your threads to run on a single processor. A processor never sees its own memory effects out of order, even when threads are pre-empted and scheduled at arbitrary times.

Memory ordering

As the flowchart suggests, any time you do lock-free programming for multicore, and your environment does not guarantee sequential consistency, you must consider how to prevent memory reordering.

On today’s architectures, the tools to enforce correct memory ordering generally fall into three categories, which prevent both compiler reordering and processor reordering:

- A lightweight sync or fence instruction, which I’ll talk about in future posts;

- A full memory fence instruction, which I’ve demonstrated previously;

- Memory operations which provide acquire or release semantics.

Acquire semantics prevent memory reordering of operations which follow it in program order, and release semantics prevent memory reordering of operations preceding it. These semantics are particularly suitable in cases when there’s a producer/consumer relationship, where one thread publishes some information and the other reads it. I’ll also talk about this more in a future post.

different processors have different memory models

different CPU families have different habits when it comes to memory reordering. The rules are documented by each CPU vendor and followed strictly by the hardware. For instance, PowerPC and ARM processors can change the order of memory stores relative to the instructions themselves, but normally, the x86/64 family of processors from Intel and AMD do not. We say the former processors have a more relaxed memory model.

In any case, keep in mind that memory reordering can also occur due to compiler reordering of instructions.

其他

一、无锁算法

CAS(比较与交换,Compare and swap) 是一种有名的无锁算法。无锁编程,即不使用锁的情况下实现多线程之间的变量同步,也就是在没有线程被阻塞的情况下实现变量的同步,所以也叫非阻塞同步(Non-blocking Synchronization)。实现非阻塞同步的方案称为“无锁编程算法”( Non-blocking algorithm)。 相对应的,独占锁是一种悲观锁,synchronized就是一种独占锁,它假设最坏的情况,并且只有在确保其它线程不会造成干扰的情况下执行,会导致其它所有需要锁的线程挂起,等待持有锁的线程释放锁。 使用lock实现线程同步有很多缺点:

-

产生竞争时,线程被阻塞等待,无法做到线程实时响应。

-

dead lock,死锁。

-

live lock。

-

优先级翻转。

-

使用不当,造成性能下降。

当然在部分情况下,目前来看,无锁编程并不能替代 lock。

二、实现级别

非同步阻塞的实现可以分成三个级别:wait-free/lock-free/obstruction-free。

- wait-free 是最理想的模式,整个操作保证每个线程在有限步骤下完成。 保证系统级吞吐(system-wide throughput)以及无线程饥饿。 截止2011年,没有多少具体的实现。即使实现了,也需要依赖于具体CPU。

- lock-free 允许个别线程饥饿,但保证系统级吞吐。确保至少有一个线程能够继续执行。 wait-free的算法必定也是lock-free的。

- obstruction-free 在任何时间点,一个线程被隔离为一个事务进行执行(其他线程suspended),并且在有限步骤内完成。在执行过程中,一旦发现数据被修改(采用时间戳、版本号),则回滚。也叫做乐观锁,即乐观并发控制(OOC)。事务的过程是:1读取,并写时间戳;2准备写入,版本校验;3校验通过则写入,校验不通过,则回滚。 lock-free必定是obstruction-free的。

三、CAS算法

CAS(比较与交换,Compare and swap) 是一种有名的无锁算法。CAS, CPU指令,在大多数处理器架构,包括IA32、Space中采用的都是CAS指令,CAS的语义是“我认为V的值应该为A,如果是,那么将V的值更新为B,否则不修改并告诉V的值实际为多少”,CAS是项 乐观锁 技术,当多个线程尝试使用CAS同时更新同一个变量时,只有其中一个线程能更新变量的值,而其它线程都失败,失败的线程并不会被挂起,而是被告知这次竞争中失败,并可以再次尝试。CAS有3个操作数,内存值V,旧的预期值A,要修改的新值B。当且仅当预期值A和内存值V相同时,将内存值V修改为B,否则什么都不做。 java.util.concurrent.atomic中的AtomicXXX,都使用了这些底层的JVM支持为数字类型的引用类型提供一种高效的CAS操作,而在java.util.concurrent中的大多数类在实现时都直接或间接的使用了这些原子变量类,这些原子变量都调用了 sun.misc.Unsafe 类库里面的 CAS算法,用CPU指令来实现无锁自增,JDK源码:

public final int getAndIncrement() {

for (;;) {

int current = get();

int next = current + 1;

if (compareAndSet(current, next))

return current;

}

}

public final boolean compareAndSet(int expect, int update) {

return unsafe.compareAndSwapInt(this, valueOffset, expect, update);

}因而在大部分情况下,java中使用Atomic包中的incrementAndGet的性能比用synchronized高出几倍。

四、ABA问题

thread1意图对val=1进行操作变成2,cas(val,1,2)。 thread1先读取val=1;thread1被抢占(preempted),让thread2运行。 thread2 修改val=3,又修改回1。 thread1继续执行,发现期望值与“原值”(其实被修改过了)相同,完成CAS操作。 使用CAS会造成ABA问题,特别是在使用指针操作一些并发数据结构时。 解决方案 ABAʹ:添加额外的标记用来指示是否被修改。 从Java1.5开始JDK的atomic包里提供了一个类AtomicStampedReference来解决ABA问题。这个类的compareAndSet方法作用是首先检查当前引用是否等于预期引用,并且当前标志是否等于预期标志,如果全部相等,则以原子方式将该引用和该标志的值设置为给定的更新值。

Hazard Pointer可以解决

CAS引发的两个问题

CAS 操作包含三个操作数 —— 内存位置(V)、预期原值(A)和新值(B)。如果内存地址里面的值和A的值是一样的,那么就将内存里面的值更新成B。CAS是通过无限循环来获取数据的,若果在第一轮循环中,a线程获取地址里面的值被b线程修改了,那么a线程需要自旋,到下次循环才有可能机会执行。

在JVM中的CAS操作就是基于处理器的CMPXCHG汇编指令实现的,因此,JVM中的CAS的原子性是处理器保障的。

ABA问题

ABA问题是指在CAS操作时,其他线程将变量值A改为了B,但是又被改回了A,等到本线程使用期望值A与当前变量进行比较时,发现变量A没有变,于是CAS就将A值进行了交换操作,但是实际上该值已经被其他线程改变过,这与乐观锁的设计思想不符合。ABA问题的解决思路是,每次变量更新的时候把变量的版本号加1,那么A-B-A就会变成A1-B2-A3,只要变量被某一线程修改过,改变量对应的版本号就会发生递增变化,从而解决了ABA问题。

CAS自旋导致的开销

多个线程争夺同一个资源时,如果自旋一直不成功,将会一直占用CPU。

解决方法:破坏掉for死循环,当超过一定时间或者一定次数时,return退出。JDK8新增的LongAddr,和ConcurrentHashMap类似的方法。当多个线程竞争时,将粒度变小,将一个变量拆分为多个变量,达到多个线程访问多个资源的效果,最后再调用sum把它合起来。