Basic Idea

We would like to execute a series of instructions atomically, but due to the presence of interrupts on a single processor (or multiple threads executing on multiple processors concurrently), we couldn’t. So we need the lock. Programmers annotate source code with locks, putting them around critical sections, and thus ensure that any such critical section executes as if it were a single atomic instruction.

lock_t mutex; // some globally-allocated lock 'mutex'

...

lock(&mutex);

balance = balance + 1;

unlock(&mutex);How to build a Spin lock

By now, you should have some understanding of how a lock works, from the perspective of a programmer. But how should we build a lock? What hardware support is needed? What OS support?

Evaluating Locks

- The first is whether the lock does its basic task, which is to provide mutual exclusion.

- The second is fairness. Does each thread contending for the lock get a fair shot at acquiring it once it is free?

- The final criterion is performance, specifically the time overheads added by using the lock.

- no contention, when a single thread is running and grabs and releases the lock, what’s the overhead?

- multiple threads are contending for the lock on a single CPU

- how does the lock perform when there are multiple CPUs involved, and threads on each contending for the lock?

Controlling Interrupts

The earliest solutions used to provide mutual exclusion was to disable interrupts for critical sections. This solution was invented for single-processor systems.

void lock() {

DisableInterrupts();

}

void unlock() {

EnableInterrupts();

}Positive:

- easy, don’t have to scratch your head too hard to figure out why this works.

Negatives:

- allow any calling thread to perform privileged operation(turning interrupts on and off)

- if one greedy program could call lock() at the beginning of its execution and thus monopolize the process

- worse, call lock() and go into an endless loop, the OS can’t regain the control of the system

- does not work on multiprocessors

- turning off interrupts for extended periods of time can lead to interrupts becoming lost, which can lead to serious systems problems.

- inefficient

So this approach is not fact. Turning off interrupts is only used in limited contexts as a mutual-exclusion primitive.

A failed attempt: Just using loads/stores

typedef struct ___lock_t { int flag; } lock_t;

void init(lock_t *mutex) {

mutex->flag = 0;

}

void lock(lock_t *mutex) {

while(mutex->flag == 1); // spin-wait (do nothing)

mutex->flag = 1;

}

void unlock(lock_t *mutex) {

mutex->flag = 0;

}The idea is simple: use a simple variable to indicate whether some thread has possession of a lock.

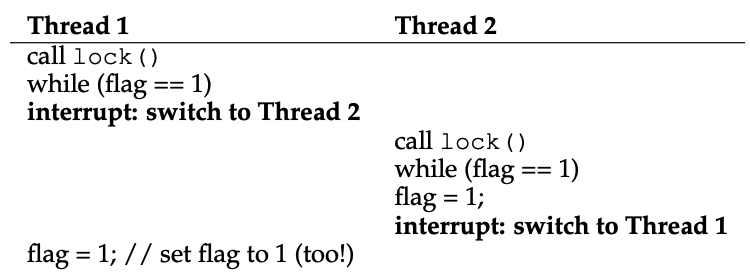

But it’s wrong. As you can see the above pic, both threads set the flag to 1 and both threads are thus bale to enter the critical secion.

Building working spin locks with test-and-set

As disabling interrupts does not work on multiple processors, and because simple approaches using loads and stores (as shown above) don’t work, system designers started to invent hardware support for locking.

test-and-set(atomic exchange) instruction. We use the follow cpp snippet code to describe:

int TestAndSet(int *old_ptr, int new) {

int old = *old_ptr;

*old_ptr = new;

return old

}What the test-and-set instruction does is as follows.

typedef struct ___lock_t { int flag; } lock_t;

void init(lock_t *lock) {

lock->flag = 0;

}

void lock(lock_t *lock) {

while(TestAndSet(&lock->flag, 1) == 1);

}

void unlock(lock_t *lock) {

lock->flag = 0;

}Rethinking last section’s problem, as the test-and-set is atomically operation, that problem never happen.

It’s the simplest type of lock to build, and simply spins, using CPU cycles, until the lock becomes available. To work correctly on single processor, it requires a preemptive scheduler(i.e., one that will interrupt a thread via a timer, in order to run a different thread, from time to time).

Evaluating Spin Locks

- Correctness. ✅

- Fairness? ❌, spin locks don’t provide any fairness guarantees.

- Performance?

- single processor: waste of CPU cycles

- multiple CPUs, work reasonably well (if the number of threads roughly equals the number os CPUs). The critical section is short, and spin thread soon require the lock, avoid the thread context swap

Compare-and-swap

Another hardware primitive that some systems provide is known as the compare-and-swap instruction.(or compare-and-exchange). The C pseudocode is below:

int CompareAndSwap(int *ptr, int expected, int new) {

int original = *ptr;

if (original == expected) {

*ptr = new;

}

return original;

}

void lock(lock_t *lock) {

while(CompareAndSwap(&lock->flag, 0, 1) == 1);

}Although, compare-and-swap is more powerful instruction than test-and-set in the situation of lock-free synchronization. However, if we just build a simple spin lock with it, its behavior is identical to the spin lock we analyzed above.

Load-linked and Store-conditional

MIPS architecture, for example, the load-linked and store-conditional instructions can be used in tandem to build locks and other concurrent structures. The C pseudocode for these instructions is as below. Alpha, PowerPC, and ARM provide similar instructions.

int LoadLinked(int *ptr) {

return *ptr;

}

int StoreConditional(int *ptr, int value) {

if (no update to *ptr since LoadLinked to this address) {

*ptr = value;

return 1;

} else {

return 0;

}

}The lock can be built as below.

void lock(lock_t *lock) {

while(1) {

while(LoadLinked(&lock->flag) == 1); // spin until it's zero

if (StoreConditional(&lock->flag, 1) == 1) return;

}

}Smart undergraduate student suggested a more concise form of the above.

void lock(lock_t *lock) {

while(LoadLinked(&lock->flag) || !StoreConditional(&lock->flag, 1));

}Fetch-and-add

One final hardware primitive is the fetch-and-add instruction, which atomically increments a value while returning the old value at a particular address. The C pseudocode look like this:

int FetchAndAdd(int *ptr) {

int old = *ptr;

*ptr = old + 1;

return old;

}We can use fetch-and-add to build a more interesting ticket lock.

typedef struct __lock_t {

int ticket;

int turn;

} lock_t;

void lock_init(lock_t *lock) {

lock->ticket = 0;

lock->turn = 0;

}

void lock(lock_t *lock) {

int myturn = FetchAndAdd(&lock->ticket);

while(lock->turn != myturn); // spin

}

void unlock(lock_t *lock) {

lock->turn = lock->turn + 1;

}Note one important difference with this solution versus our previous attempts: it ensures progress for all threads. Once a thread is assigned its ticket value, it will be scheduled at some point in the future(once those in front of it have passed through the critical section and released the lock).

How to avoid spinning

Simple approach: just yield

Our first try is simple and friendly approach: when you are going to spin, instead give up the CPU to another thread.

void init() {

flag = 0;

}

void lock() {

while(TestAndSet(&flag, 1) == 1)

yield();

}

void unlock() {

flag = 0;

}Yield is simply a system call that moves the caller from the running state to the ready state, and thus promotes another thread to running.

But, we have not tackled the starvation problem at all.

Using queues: sleeping instead of spinning

The real problem with our previous approaches is that they leave too much to change. The scheduler determines which thread runs next; if the scheduler makes a bad choice, a thread runs that must either spin waiting for the lock (our first approach), or yield the CPU immediately (our second approach). Either way, there is potential for waste and no prevention of starvation.

Thus, we must explicitly exert some control over which thread next gets to acquire the lock after the current holder releases it. A queue to keep track of which threads are waiting to acquire the lock

spin lock maybe cause priority inversion.

Assume T1, T2, and T1 has lower priority. T1 only runs when T2 is not able to do so(e.g. when T2 is blocked on I/O). Now the problem. Assume T2 is blocked for some reason. So T1 runs, grabs a spin lock, and enters a critical section. T2 now become unblocked, and the CPU scheduler immediately schedules it. Now T2 tries to acquire the lock, and it can’t, it just keeps spinning. Because the lock is a spin lock, T2 spins forever, and the system is hung.solution is: priority inheritance, more generally, a higer-priority thread waiting for a lower-priority thread can temporarily boost the lower thread’s priority, thus enabling it to run and overcoming the inversion.

Linux provides a futex which is similar to the Solaris interface but provides more in-kernel functionality. Specifically, each futex has associated witch it a specific physical memory location, as well as a per-futex in-kernal queue. Callers can use futex call to sleep and wake as need be.

void mutex_lock(int *mutex) {

int v;

// bit 31 was clear, we got the mutex

if (atomic_bit_test_set(mutex, 31) == 0) return;

atomic_increment(mutex);

while(1) {

if (atomic_bit_test_set(mutex, 31) == 0) {

atomic_decrement(mutex);

return;

}

// we have to waitfirst make sure the futex value we monitoring is truly negative(locked)

v = *mutex;

if (v >= 0) continue;

futex_wait(mutex, v);

}

}

void mutex_unlock(int *mutex) {

// adding 0x80000000 to counter results in 0 if and only if there are not other intersted threads

if (atomic_add_zero(mutex, 0x80000000)) return;

// there are other threads waiting for this mutex, wake one of them up.

futex_wake(*mutex);

}Two-phase locks

One final note: the Linux approach has the flavor the an old approach , and is now referred to as a two-phase lock. A two-phase lock realizes that spinning can be useful, particularly if the lock is about to be released. So in the first phase, the lock spins for a while, hoping that is can acquire the lock.

However, if the lock is not acquired during the first spin phase, a second phase is entered, where the caller is put to sleep, and only woken up when the lock becomes free later. The Linux lock above is a form of such a lock, but it only pins once; a generalization of this could spin in a loop for a fixed amount of time before using futex support to sleep.

两阶段锁,是 hybrid 方法的一个很好实例,结合两个好想法变成更好的一个方法。当然这取决于很多因素,硬件环境,线程数量,工作负载情况。总之,做一个通用的适用于所有情况的锁仍然是一个挑战。