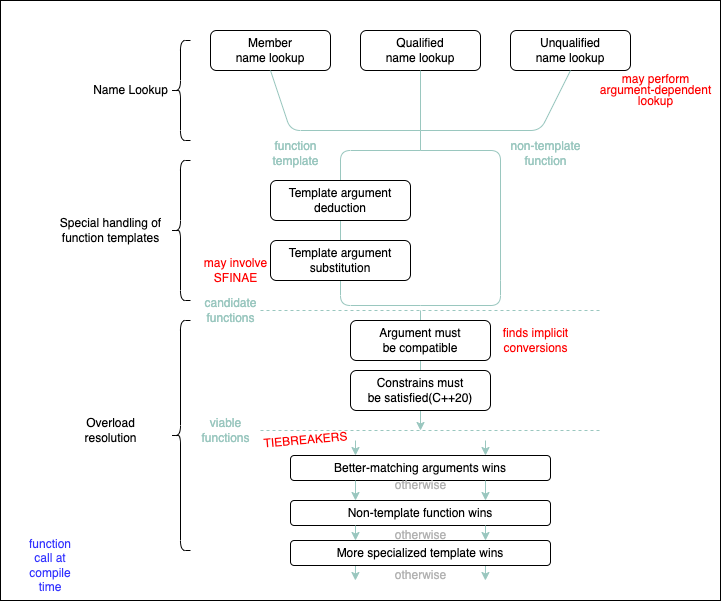

This is how the compiler, given a function call expression, figures out exactly which function to call. These steps are enshrined in the C++ standard. Every C++ compiler must follow them, and the whole thing happens at compile time for every function call expression evaluated by the program.

I imagine the overall intent of the algorithm is to “do what the programmer expects”, and to some extent, it’s successful at that. You can get pretty far ignoring the algorithm altogether.

Name Lookup

namespace galaxy {

struct Asteroid {

float radius = 12;

};

void blast(Asteroid* ast, float force);

}

struct Target {

galaxy::Asteroid* ast;

Target(galaxy::Asteroid* ast): ast{ast} {}

operator galaxy::Asteroid*() const {return ast;}

};

bool blast(Target target);

template<typename T> void blast(T* obj, float force);

void play(galaxy::Asteroid* ast) {

blast(ast, 100);

}There are three main types of name lookup:

- Member name lookup occurs when a name is to the right of a

aor->token, as infoo->bar. This type of lookup is used to locate class members - Qualified name lookup occurs when a name has a

::token in it, likestd::sort. This type of name is explicit. The part to the right of the::token is only looked up in the scope identified by the left part. - Unqualified name lookup is neither of those. When the compiler sees an unqualified name, like

blast, it looks for matching declarations in various scopes depending on the context. There’s a detailed set of rules that determine exactly where the compiler should look.

In our case, we have an unqualified name. Now when name lookup is performed for a function call expression, the compiler may find multiple declarations. Let’s call these declarations candidates. In the example above, the compiler finds three candidates:

void galaxy::blast(galaxy::Asteroid* ast, float force);

bool blast(Target target);

template<typename T> void blast(T* obj, float force);The first candidate, deserves extra attention because is demenstrates a feature of C++ that’s easy to overlook: argument-dependent lookup, or ADL for short. Here’s a quick summary in case you’re in the same boat. Normally, you wouldn’t expect this function to be a candidate for this particular call, since it was declared inside the galaxy namespace and the call comes from outside the galaxy namespace. There’s no using namespace galaxy directive in the code to make this function visible, either. So why is this function a candidate?

The reason is because any time you use an unqualified name in a function call – and the name doesn’t refer to a class member, among other things – ADL kicks in, and name lookup becomes more greedy. Specifically, in addition to the usual places, the compiler looks for candidate functions in the namespaces of the argument types – hence the name “argument-dependent lookup”.

The complete set of rules governing ADL is more nuanced than what I’ve described here, but the key thing is that ADL only works with unqualified names. For qualified names, which are looked up in a single scope, there’s no point. ADL also works when overloading built-in operators like + and ==, which lets you take advantage of it when writing, say, a math library.

Interestingly, there are cases where member name lookup can find candidates that unqualified name lookup can’t. See this post by Eli Bendersky for details about that.

Special handling of function template

Some of the candidates found by name lookup are functions; others are function templates. There’s just one problem with function templates: You can’t call them. You can only call functions. Therefore, after name lookup, the compiler goes through the list of candidates and tries to turn each function template into a function.

Overload resolution

At this stage, all of the function templates found during name lookup are gone, and we’re left with a nice, tidy set of candidate functions. This is also referred to as the overload set. Here’s the updated list of candidate functions for our example:

void galaxy::blast(galaxy::Asteroid* ast, float force);

bool blast(Target target);

void blast<galaxy::Asteroid>(galaxy::Asteroid* obj, float force);The next two steps narrow down this list even further by determining which of the candidate functions are viable – in other words, which ones could handle the function call.

After using the caller’s arguments to filter out incompatible candidates, the compiler proceeds to check whether each function’s constraints are satisfied, if there are any. Constraints are a new feature in C++20. They let you use custom logic to eliminate candidate functions (coming from a class template or function template) without having to resort to SFINAE. They’re also supposed to give you better error messages. Our example doesn’t use constraints, so we can skip this step. (Technically, the standard says that constraints are also checked earlier, during template argument deduction, but I skipped over that detail. Checking in both places helps ensure the best possible error message is shown.)

Tiebreakers

At this point in out example, we’re down to two viable functions. Either of them could handle the original function call just fine:

void galaxy::blast(galaxy::Asteroid* ast, float force);

void blast<galaxy::Asteroid>(galaxy::Asteroid* obj, float force);Indeed, if either of the above functions was the only viable one, it would be the one that handles the function call. But because there are two, the compiler must now do what it always does when there are multiple viable functions: It must determine which one is the best viable function. To be the best viable function, one of them must “win” against every other viable function as decided by a sequence of tiebreaker rules.

First tiebreaker: Better-matching parameters wins

the two method are identical parameter types. So neither is better than the other.

Second tiebreaker: Non-template function wins

So the first method wins.

Third tiebreaker: More specialized template wins

If it wasn’t found, we would move on to the third tiebreaker.

There are several more tiebreakers in addition to the ones listed here. For example, if both the spaceship <=> operator and an overloaded comparison operator such as > are viable, C++ prefers the comparison operator. And if the candidates are user-defined conversion functions, there are other rules that take higher priority than the ones I’ve shown. Nonetheless, I believe the three tiebreakers I’ve shown are the most important to remember.

Needless to say, if the compiler checks every tiebreaker and doesn’t find a single, unambiguous winner, compilation fails with an error message similar to the one shown near the beginning of this post.

After the function call is resolved

We’ve reached the end of our journey. The compiler now knows exactly which function should be called by the expression blast(ast, 100). In many cases, though, the compiler has more work to do after resolving a function call:

- If the function being called is a class member, the compiler must check that member’s access specifiers to see if it’s accessible to the caller.

- If the function being called is a template function, the compiler attempts to instantiate that template function, provided its definition is visible.

- If the function being called is a virtual function, the compiler generates special machine instructions so that the correct override will be called at runtime.